During the period from 1650 to 1750 bricks were Medford’s chief business. They were loaded onto lighters, floated down the Mystic to Boston and from there shipped to all parts of the colonies.

Kilns and Clay

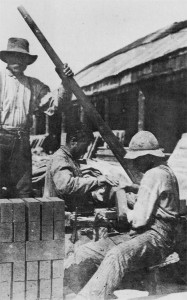

Aug. 5, 1891, College Hill brickyard.

The first settlers of Massachusetts intended to build a permanent plantation. They were practical people so many skilled artisans were among the immigrants. One of the first things they did was to look for suitable sources of clay and to begin manufacturing bricks for use in house construction. Medford quickly proved to have abundant quantities of good clay, so it is not surprising that a bricklayer was among the earliest settlers here.

Thomas Eames, who had been in Dedham by 1640, was living in Medford by 1652, when he was 34 years old. Eight years later he took young Joseph Mirrible as an apprentice, agreeing to teach him how to make and lay bricks, also how to write and reckon his accounts. Eames moved on to Sudbury by 1664, but there were many other brickmakers to take his place, and Medford became a center for the manufacture of brick.

Joseph Squire was one of these. In 1697 he sold John Pratt of Boston 1500 “hard bricks” at 30 shillings per thousand and 1100 “Samin bricks” for 13 shillings per thousand. These “Samin” bricks may have been “salmon” in color, but more likely were a cheaper brick intended for wall fill.

During the period from 1650 to 1750 bricks were Medford’s chief business. They were loaded onto lighters, floated down the Mystic to Boston and from there shipped to all parts of the colonies. Although other industries diversified Medford’s trade, brickmaking was basic to it for many years.

April 30. 1897, College Hill brickyard.

There were brickyards all over the town. Thomas Eames worked land in West Medford in 1660. His brickyards were south of Boston Avenue between Arlington Street and the Mystic River. Thomas Brooks made bricks on this same land in the 18th century. Quite early, bricks were made from clay deposits near the Royall House. In 1714 Stephen Willis, Jr. maintained a brickyard on the site of the old high school on Forest Street. Caleb Brooks made bricks near the second Meeting House. Ashland Street was called “a way to the clay land.”

There was a great brickyard on each side of Fulton Street extending from Forest Street to the Maiden line. This was called the Fountain yards, named after the nearby Fountain Tavern. There was a yard near the Weir bridge, though it had only one kiln, and another yard at the foot of Winter Hill.

Halfway between Rock Hill and the Boston and Maine Railroad was a yard where Samuel Francis made bricks as early as 1750. He sold them at ten shillings a thousand. A decade later Thomas Brooks was carrying on this business and selling bricks for fifteen shillings a thousand. By 1759 the price had increased to four dollars a thousand.

South of the Mystic River were the “Sodom” yards. These were located between Summer and George Streets near the Middlesex Canal. The road to them was naturally called Brickyard Lane. The Tufts family made brick here. Up near Tufts University opposite Cousens Gymnasium on College Avenue was another yard. John Russell and Son worked here as did William and John Maxwell. This brickyard was still being used in the twentieth century.

1892.

A major brickyard was that owned by the Bay State Brick Company on Riverside Avenue. Many of the labor force employed in this yard were migrant workers from French Canada. They lived in crowded boarding houses or in houses “packed in closely on both sides” on Linden Street, Locust Street, and Hall Avenue off Riverside Avenue. Many brought their families. The locals referred to them as living in the brickyards.

A “representative” of the Medford Mercury visited this area on a moonlit night in September, 1899. The representative found few lights in the houses which looked deserted. But there were men and boys playing games in a nearby field with “loud laughter and shouting.” The houses were quite small, often only one room on the ground floor. Outside one house a couple was talking and holding hands. Clearly, this was a tenement area with its own charms.

The migrant laborers worked from early springtime to early fall. In the late summer they dug out the clay from the pits and placed it in piles to weather through the winter. This made the clay more pliable when work resumed in the spring. Then it was taken and spread out on the ground. In the early days workers would water these piles, then trod on them to make the clay easier to turn into bricks. Later oxen and horses took over this task.

Aug. 5, 1891, College Hill brick yard.

The brick business was profitable for Medford bricks were of an excellent quality and much in demand. Toward the close of the nineteenth century, between 15 million and 20 million bricks were made each year by the Bay State Brick Company. On November 23, 1900 the name was changed when the original company was purchased by the New England Brick Company.

The New England Brick Company yards, were located on the western side of Riverside Ave. It reorganized in 1923 but was eventually closed “forever and a day” as the Medford Mercury phrased it in the late 1920’s. In 1930 the wooden firing sheds were torn down and the equipment of the company moved to its Cambridge plant. An era in Medford had ended.

But not completely. Left behind were the pits from which the clay had been dug. These filled with rain water and debris and were’ ‘eyesores” to the citizens. One, at least, was used by the city as a dump. Further, the pits were a danger because youngsters found them convenient places to swim. Over the years too many of them drowned in these pits.

During the Civil War, Deacon W.W. Babbitt gave 500 Medford bricks to be auctioned off to help the soldiers. The money was used as a recruiting fund by the town. The first brick sold for ten dollars; the 164th for seventy- five dollars. How much would people pay today for a genuine Medford brick?

Text and photos from Medford on the Mystic. By Carl Seaburg and Alan Seaburg. Published by The Medford Historical Society, April 1980.