The changes came slowly at first, then faster, and finally they came inevitably.

The changes came slowly at first, then faster, and finally they came inevitably. Religious outlooks changed. The established Congregational church split as the theology of some members liberalized and the theology of others remained traditional. At the same time, this church lost its prominent position in the community. Changes in transportation were evident as the Middlesex Canal was built through the town, used for many years, then was overtaken by the speed and economy of the new railroad. Industries were established which supported an increasing population. Medford acquired a reputation for superior ship-building. This industry dominated the life of the town for three-quarters of the century.

Town boundaries changed too. In 1811 a small portion of land was annexed to Charlestown. The western end of Wellington farm was acquired from Maiden in 1817. The newly created town of Winchester received land from Medford in 1850, the section which had been called “Upper Medford.” Another section of Wellington farm in Everett was added to Medford in 1875. Two years later a small section east of the present Stevens Square became part of Maiden. By the end of the century Medford was approximately its present size of 8.22 square miles.

Several new bridges were built in this century but the one that got the most attention was the old bridge in the Square. In 1808 it was rebuilt after several years of debate. The new bridge had a draw and the first year it cost 12’/2 cents to pass through. The fee was changed to correspond to the size of the vessel. In 1829 the town meeting appointed a committee to study the bridge, which decided to eliminate the draw. But since one of the town’s shipyards was located upriver west of the bridge this was not practical. So the draw stayed. In 1853 it was made some forty feet wide. After the shipyards went out of business the present stone bridge across the Mystic was constructed in 1880 and given the name of Cradock Bridge.

The same ill fortune beset the Andover Turnpike. This direct road from Andover through Reading and Stoneham to the bridge in Medford saved three miles of travel for teamsters. A company to build it was incorporated in 1805. Its expenses later proved to be greater than the revenue it yielded and by 1828 the stockholders wanted to unload it. There were no purchasers. Two years later it was given to the towns it passed through. The Medford section became Forest Street and Fellsway West.

In the last quarter of the century as farms were sold and turned into developments, more new roads were constructed. By 1905 there were 156 accepted streets with a total length of 51.5 miles.

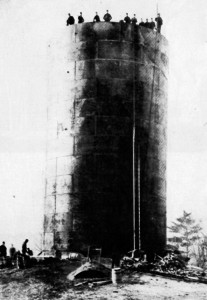

The new railroad changed the town even more than the Middlesex Canal had. The railroad brought money into the town, increased property values, and added — what the quietly floating canal boats had not — a preview of the noise of the twentieth century. The Boston and Lowell Railway was chartered on June 5, 1830. A year later the surveyors went through Medford; the construction gangs followed and in 1835 the route was opened to the public. Ten years later the Medford branch of the Boston & Maine was constructed with a terminal in Medford Square. A conductor on one of these early trains, Charles B. George, described it as consisting of “a small cabless engine, the ‘Medford,’ weighing about five tons, and the train was made up of a single car, which was baggage and passenger car combined.” The smoke and hooting of the railroad became part of the Medford landscape for many years.

The full impact of the changes that came to Medford in this century were felt in the last half. Up until 1850 Medford was still essentially a quiet country town. It had experienced remotely the War of 1812 with England, but neither Medford nor New Englanders generally were in favor of this war and tended to ignore it as much as they could. Yet, as Medford had always done, it sent its quota of men to serve in the militia and in the army and navy. Three of them were killed. But this was a war quickly forgotten.

The town took pride in the fact that a Medford citizen was seven times elected to one year terms as Governor of the Commonwealth. John Brooks, of Revolutionary War renown, brought further laurels upon himself by his political career. People did not forget that one of his sons had been killed in that second war with England.

In the first part of the century, there was no water department. People either used their own well or got water from the town pump. Someone remembering Medford at this time said that while Boston had had hot and cold running water for two years, there wasn’t such a thing “as a bathroom or bathtub in the town.”

Town regulations promoted this ideal of a quiet pastoral town. There was to be no bathing in “exposed places;” “fast driving” was prohibited; and dogs were forbidden to “disturb any neighborhood.” What success there was in regulating dogs is uncertain. If you threw snowballs in the public streets which annoyed others, why you paid the town a fine of five dollars. One had to live properly in the Medford of 1850. Yet, “one day was very much like another in old Medford. It was seldom that anything sensational occurred… The town wasn’t as much of a bedroom for Boston business men as now. True, there were many who did business in the city and went in daily, but the great majority found work enough to do at home. There was much sociability in the old time and everybody knew everybody else.”

Still there were exciting moments to report. Through the years there had been few large fires in the town. One great inferno occurred on the night of November 21, 1850. It swept through the buildings on Main Street and the neighborhood between the bridge and South Street. The wind carried the fire quickly and made crossing the bridge impossible. Ten or fifteen engines came from neighboring towns but couldn’t get across the bridge. By 2 a.m. thirty-six buildings, houses, workshops, and barns had been reduced to ashes. The loss was $36,000.

The next year there was another violent event when a tornado swept through the town. It struck late in the afternoon of August 22nd, entering Medford near the Weirs bridge, then moving along easterly into Malden. There was extensive destruction to property and homes. Many trees were toppled; roofs, boards, shingles, slate, and chimneys were scattered about in the ruins. The damage amounted to nearly $19,000.

There was no local newspaper to report the vicissitudes of this country town, however, until the Medford Journal, began publishing in 1857. It lasted only three months. Thirteen years later another Medford Journal was begun. Following this came the Citizen and the Leader but none of these survived. In 1872 the Medford Chronicle was started. This merged in 1882 with the Medford Mercury which had come out in 1880 and proved to be the most enduring of them all.

The educational needs of the town changed in this century as the populaton increased. Perhaps one of the most significant educational developments was the decision in 1835 to grade the schools. This resulted in the construction of the first high school in town (which some people thought was a waste of time and money), two grammar schools, and one or more primary schools. A college was also established on Walnut Hill by the Universalist denomination. Tufts College opened its doors in 1852.

In 1825 the Medford Social Library, a circulating library, was organized. Shares, at one dollar each, were sold to the public. Members had to pay an annual fee of 50 cents which permitted the shareholder to take out two books at a time. This institution served the community for thirty years. In 1855 it was decided to establish a public library on the condition that the collection of the Social Library be transferred to the public library. An agreement was reached and the town voted $350 toward the project.

The present site became the location of the library when Thatcher Magoun Jr. wrote the selectmen in 1875 and offered to the town his father’s imposing mansion as a home for the town library. He also gave $1,000 to help equip the library. The town accepted his generous offer and the library moved into its new quarters. In 1897 a “stock” room was added to the rear of the building to hold 60,000 volumes. Branch deliveries were established in various parts of the city to make the library more useful to the citizens. By the end of the century the library had over 16,000 books and a yearly circulation of 51,000 volumes.

The Civil War was one of the decisive events of this century that brought changes to Medford as well as to the country. As early as 1837 the problems of slavery had been discussed, over some opposition, in the town. The discussion continued and increased in vehemence, in Medford and the nation.

Perhaps the Medford person most dramatically involved in anti-slavery activity was George Luther Stearns. He was a “big, solemn merchant” who owned a “linseed oil mill, cleared from $15,000 to $20,000 a year in profits, and lived in a luxurious Tuder-style mansion” near what is now Cousens Gym at Tufts University. John Brown, who raided Harper’s-Ferry, Virginia in 1859 in an effort to free the enslaved blacks, was his friend. Steams was more than a friend to Brown’s cause. He was one of the “Secret Six” who gave moral and financial support to Brown in his raid. For Stearns shared Brown’s conviction that slavery was so evil an institution that it had to be destroyed by any means possible. Brown had been to his house and shared his plans with Stearns. And the Stearns home had been a stop on the “underground railroad” which helped fugitive slaves escape their cruel masters and find freedom in Canada. After Brown’s arrest, Stearns fled to Canada.

Slavery came to an end only after the south threatened to destroy the Union. Medford responded to President Lincoln’s numerous calls for troops to defend the United States. The Lawrence Light Guard, organized in 1854 as Company E of the Fifth Massachusetts Light Infantry, was ready when Lincoln’s first call came. Under the leadership of Col. Samuel Crocker Lawrence and Captain John Hutchins, the Guard left for the south. They assisted in the protection of the capital and took part in the First Battle of Bull Run. Their Colonel was wounded in this battle. After their three months duty, they were mustered out of service.

In 1862 Lincoln again called for more men. Once more Medford sent the Lawrence Light Guard. The armory was opened as a recruiting office and one hundred and one men signed on for three years. In 1863 they were in Washington serving with other units as part of the Provost Guard. That July they were a part of the Army of the Potomac. Their career was colorful and some of their men were killed, others wounded, or taken prisoner by the Confederates. They did not return to Medford until June 1865. Besides the Guard, other Medford men served. President Lincoln issued eleven calls for men, and a total of 769 men responded from Medford.

Medford was changing in this century but the population did not increase until the large landholdings began to be broken up. From Gov. Cradock’s time on, large chunks of Medford had been in the hands of a few people. Not until these estates came on the market and could be divided and sold for small house lots was there much possibility of population growth.

Around mid-century this began to happen. Lands in West Medford from Woburn Street to the railroad came on the market in 1844. That same year the Tufts estate at Salem and Forest streets, was divided. Real estate developers like the Edgeworth Company and Hall & Dow came on the scene and opened up Sagamore Vale and the Bishop estate. By 1855, Wellington Farms and the Hall farm in East Medford and the T. P. Smith estate in West Medford were being sub-divided.

At the same time that land was becoming available for small home owners, transportation improvements were being made. One development affected the other. Travel between Medford and Boston became easier and quicker. The railroad was better for this purpose than the Middlesex Canal, but the streetcar was still cheaper and more convenient than the railroad.

A horse street railway between Medford and Charlestown running through Somerville was incorporated in 1855 and in operation by 1860. It suspended operations for fourteen years from 1869 to 1883 because the Somerville selectmen objected to the location of the tracks on Somerville streets. It was reopened in 1883 when the three towns agreed to pay the cost of paving the roadbed. Eventually this line was extended to Malden. A second horse railway began operations between Medford Square and West Medford in 1887.

By that year horse railways were available everywhere. “By changing cars a few times,” reported the Medford Mercury on Aug. 19, 1887, “one can go to either Lynn, Peabody, Marblehead, Salem or Beverly.”

By 1897 two West End Street Railway company lines were running-out of Medford, one to Scollay Square in Boston and the other to Everett Square. “Electrics,” however, required overhead lines and wider and straighter streets. Double tracks were needed to provide more frequent transportation. The “cars” brought people into Medford as well as taking them out of town, and the increase in land for sale gave these new people places to live.

In 1870, 150 house lots were made available in the sale of the Ebenezer Smith estate in West Medford. Land speculators were developing the Central Avenue area by 1886. The auction of the Dudley Hall estate off Forest Street in 1891 put ten acres of prime land on the market. Governor’s Avenue was opened the next year. The town was beginning to change from what it had been before the Civil War. At mid-century the population was 3,749. In 1875 it had not quite doubled to 6,267. By 1890 it was 11,770 and ten years later it hit 18,244, almost five times the size of the mid-century town. By then Medford had become a city.

Some people looked forward to Medford becoming a city, some did not. There had been rivalry for years between the eastern and western sections which went as far back as the 17th century in picking the location of the first Meeting House. This rivalry came up again in 1885 when some citizens of West Medford petitioned the General Court to allow them to form a separate and new town out of West Medford to be called “Brooks.” The new town would have consisted of all land west of Winthrop Circle. The General Court refused this petition and three other similar requests which came from “Brooks” proponents.

By 1891, hoping to keep the community united and since Medford now had enough inhabitants to become a city, the town applied to the General Court. Its petition was granted, but this action had to be accepted by the voters. The vote was favorable by a close 382 to 342.

Town government ended. Medford was now a city with a Mayor, six Aldermen a Common Council of eighteen members and other officers. In a city-wide election in December 1892, Medford’s largest land-holder and Civil War General, Samuel Crocker Lawrence, was elected the first Mayor. He took office in 1893.

How this Medford had changed! Gas lighting had been introduced in 1857. A telephone line was strung from Medford Square to West Medford in 1879 and by 1883 there was a workable telephone system in town with quite a few houses connected. Electric lights came in 1887. By 1895 the Middle- sex Fells Public Park had become a reality. In 1896 the Medford Historical Society was organized. That same year a new High School was built on Forest Street and a race track. Combination Park, opened in South Medford. Fellsway West was completed in 1898 and the same year Medford Square was paved. Why, even the city police were being supplied with flashlights! Charles Hurd noted the vivid difference between the “quiet restful suburban village with its old houses and simple ways” of his youth and this new “pushing, rapidly growing young city, which has only now just begun to feel its strength.”

If the Sprague brothers could have re-visited Medford at the end of the 19th century, they might have come by railroad from Boston or by streetcar from Salem. What surprises would have greeted their eyes in the electric lights, telephones, and paved roads. Streetcars clanged through its streets. Wagons and carts and carriages crowded the roads. A few automobiles chugged noisily along. It was no longer the quiet town they would have seen in 1800. There was an air of “get up and go” in the inhabitants who were on their way to join the complex, interwoven world of the twentieth century.

.

What did selectmen do? The list of matters that crossed their table and absorbed their mind and vexed their discussions ran the length of the alphabet. Herewith a sampling of the index to their records:

A = almhouse and assessing

B = bathing, bounds, bridges, ballplaying

C = cesspools, old cellars, cisterns, coasting on streets, killing a mad cow

D = drunkards and tipplers, dogs, drains

E = electric lights

F = fences, fireworks

G = gutters, guardians, gypsy moths

H = highways, horses, hydrants

I = incendiaries, insane, insurance

J = janitors, jurors

K = keepers of the poor house, kerosene

L = laborers, lamplighters, library, licenses

M = military, mills, militia

N = notes and nuisances

0 = offal, outside relief, overseers of the poor

P = parks, pastures, and paupers, perambulations of the town lines, pest houses, petitions, police, poor. polls, posts and pounds

Q = quorums and quotas

R = railroads, retailers, rewards, roads, and rubbish

S = saloons, scales, schools, sewerage, sidewalks, signs, snow, soldiers. stables state aid. street lights and streets

T = taxes, telephone poles, tramps, trees

U = undertakers, uniforms

V = vaccinations, vagrants, vehicles, voting

W = walls, wards, warrants, watchmen, water, weights & measures And nothing left for X. Y. and Z.

Mayors

1. Samuel C. Lawrence. 1893- 1894

2. Baxter E. Perry. 1895- 1896

3. Lewis H. Lovering, 1897-1900

4. Charles S. Baxter, 1901-1904

5. Michael F. Dwyer. 1905- 1907

6. Clifford M. Brewer. 1908- 1910

7. Charles S.Taylor, 1911-1914

8. Benjamin F.Haines, 1915- 1922

9. Richard B. Coolidge. 1923- 1926

10. Edward H. Larkin, 1927- 1931

11. John H. Burke. 1932-33

12. JohnJ.Irwin, 1934- 1937

13. John C. Can-, 1938- 1943 (Entered armed forces July 25. 1943. George L. Callahan. Acting Mayor)

14. Walter E. Lawrence, 1944- 1949

15. Frederick T.McDermott. 1950- 1951

16. JohnC.Carr.Jr.. 1952- 1954

17. Arthur DelloRusso. 1955

18. Alfred P. Pompeo, 1956- 1957

19. JohnC.Carr.Jr., 1958-1961

20. JohnJ.McGlynn. 1962- 1967

21. Patrick J. Skerry, 1968- 1969

22. JohnJ.McGlynn. 1970- 1971

23. Angelo Marotta. 1972- 1973

24. FrederickN.DelloRusso.l974

25. James K. Kurker, 1975

26. JohnJ.McGlynn. 1976- 1977

27. Eugene F. Grant, 1978- 1979

28. Paul J. Donate. 1980-

City Managers

1. James F. Shurtleff, 1950- 1956

2. John B.Kennedy. 1957- 1958

3. Edward J.Conroy, 1959- 1960

4. John C. Can-. 1961

5. Howard Reed, 1962- 1969

6. James O. Nicholson, 1970- 1980

7. Carroll P. Sheehan, 1980-

From Medford on the Mystic. By Carl Seaburg and Alan Seaburg. Published by The Medford Historical Society, April 1980.