As the population increased, Medford gradually took on the aspects of a town.

Dorothy Wellington Bartlett

Medford was a small, pleasant village at the beginning of the eighteenth century with a population of fewer than 230 people. By 1803, 1,114 persons were counted in the town in the national census of that year.

Not all residents in the town were free. In a census of Negro slaves in Massachusetts Bay in 1755, there were thirty-four enslaved people over the age of sixteen living in Medford. Twenty-seven were men and seven were women. By 1764-65 the population of enslaved peoples in Medford had increased to forty-nine.

In 1734, Medford selectmen voted that “all Negro, Indian and mulatto servants that are found abroad without leave and not on their master’s business shall be taken up and whipped ten stripes on their naked body by any freeholder of the town, and be carried to their respective masters, and said masters shall be obligated to pay the sume of 2s.,6d in money to said person that shall do so.”

Slavery was finally outlawed in 1787 in the case of Commonwealth v. Jennison. Today, there are a number of visible remnants of slavery in Medford: on Grove Street stands the “slave wall,” a brick wall capped with thin stone slabs and a granite post at the southern end. Pomp, an enslaved man of Thomas Brooks, is said to have built it around 1765; in the yard of the Royall House 35 feet from the mansion, stands the Slave Quarters. Census and probate records have preserved the names of more than 60 men, women and children enslaved by the Royalls.

Dorothy Wellington Bartlett

RELIGION

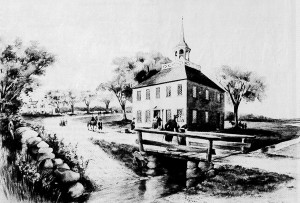

Religion was a vital part of the life of the country town. The meeting- house which had been erected just before the close of the seventeenth century served as the church for two decades into the new century. By 1716, it was overcrowded and by 1726, land was purchased from John Albree on the south side of High Street “adjoining Marble brook” and the second Meeting House was constructed for 360 pounds. Later a steeple was added.

Aaron Porter was the first settled minister. He was called in May 1712, ordained a year later, and served until his death in 1722. Samuel Sewell’ noting Porter’s death in his diary, called him, “the desirable Pastor of the Church in Meadford.” For the rest of the century only two men served as pastor.

The Reverend Ebenezer Turell was born in Boston on 5 February 1702, graduated from Harvard in 1721, and was ordained here in 1724 It was said that he “labored acceptably” until his health failed a year before the Revolution. Turell preached the dedication sermon for the second meeting house, September 3, 1727.

During his pastorate he noted that he had preached more than five thousand sermons and baptized over one thousand persons. In 1744, a bell was bought for the steeple by subscription, the first time that the parish had its own bell Town meetings were held in the meetinghouse. In 1756 a Fast Day was held because “of the surprising earthquake which we have been visited with of late.”

For forty-three years the parish worshipped in the second meeting- house. In 1768 they decided to build a new one. It was erected on the site of the present Unitarian Universalist Church formerly the First Parish at 147 High Street. Sixty-six feet long and forty-six feet wide, the church had forty-eight pews on the floor and eight pews in the gallery. The first service in the new building was held on March 11, 1770. The bell from the second meetinghouse was moved to the new tower. It tolled when the sun went down and for special solemn occasions such as George Washington’s memorial service. Past this meetinghouse Paul Revere rode in the moonlight on April 18, 1775.

In 1774, the Reverend David Osgood was hired and when Turell died in 1778, Osgood became the settled minister serving for 48 years. Under his leadership a majority of the parish became Unitarian.

The Medford Public Library holds the diaries of Rev. Osgood and MHSM houses the WPA transcriptions, which document the everyday life of the minister from Jan. 1776 to Dec. 1822.

EDUCATION

Three generations grew up in Medford before a public school was established. In 1647 the General Court of Massachusetts passed a law saying that towns of more than fifty families must maintain an elementary school. Medford ignored the law because it was below the minimum. The need for a school was not discussed until November 30, 1719 when the town voted to keep a school in the house of Thomas Willis, Jr. The first teacher, Henry Davison, was hired at a salary of three pounds per year plus board. The next year two schools were maintained, one in the eastern part of town with Davison again as teacher, another in the western part of town with Caleb Brooks as teacher. Both schools were held in private houses. The total school budget was eight pounds.

No schoolhouse was constructed until 1732; erected on “the southerly side of High Street, just east of and adjoining Marble or Meetinghouse Brook.” This school served the town until 1771 when a second one was built on land purchased from Jonathan Watson. This school was on High Street west of the third meetinghouse. Being small it was soon overcrowded and so in 1795 a larger brick school was constructed behind the First Parish.

From the 1904 watercolor by Fred H. C. Woolley, “A Sabbath Morning in 1730”

These schools were only for boys and they taught reading, writing and arithmetic. Not until 1766 were girls permitted two hours of instruction after the boys had been dismissed. Finally in 1790, girls were allowed to study with the boys — but only during the summer months.

Dr. Luther Steams, a graduate of Harvard College, opened a private school in 1791. In 1790 William Woodbridge opened a “boarding and day school in the Royall House.” At one time he had 42 boys and 96 girls. From 1795-1800 Joseph Wyman from Woburn maintained a school for both boys and girls. This was taken over by Susanne Rowson in 1800 until she moved the school t Boston in 1803.

BOUNDARIES

There were many futile attempts — 1702, 1734, 1748 — to enlarge the boundaries of the town. Medford wanted some of the land belonging to its larger neighbor, Charlestown, and finally on April 19, 1754 the General Court granted Medford 760 acres on the south side of the Mystic River. It now acquired all the land it was ever to have south of the river. By this accession some of Governor John Winthrop’s original Ten Hills Farm grant became part of Medford. His house had been located on the easterly slope near the top of Winter Hill.

The town also was granted the Charlestown woodlots, now the Medford part of the Middlesex Fells, and some land in what was then Woburn, now Winchester.

As the town grew in area and population, roads developed to accommodate people’s desire to get where they wanted to go as easily as possible. In 1803, the only direct route to Boston was the old road over the top of Winter hill through Charlestown to the Charles river bridge. It was a long, hard pull up and over the hill, not only for the local teams, but for the much greater volume of traffic and stages from northern Middlesex and New Hampshire. As a result, the level road known as the Andover turnpike would be built (six miles) from Medford Square to the Reading line. The old toll-road has become a beautiful residential street now known as Forest Street.

By 1817 a cartway to the distillery was in common use and became “Distill House Lane” (presently Riverside Avenue). Another lane ran from Salem Street to the river behind the distillery and was called “the way to the wharf” (presently River Street). In 1735 Fulton Street became a public highway and in 1746 another section of Riverside Avenue between River Street and Cross Street was established by some of the inhabitants as a way to the tide-mill.

The bridge in the square was still a matter of controversy through much of the century since No town wanted to pay for its frequent repairs. The burden for the upkeep of the northern end of the bridge was laid upon Malden, Woburn, Reading, and Medford by edict of the General Court until 1760. When Medford acquired part of Charlestown in 1754, it also had to assume responsibility for repairing the southern end of the bridge.

The bridge brought traffic and travelers. Taverns sprang up as stopping places for these travelers on business or pleasure. While much of the traffic in town was on foot or horseback, there was enough affluence that a 1753 survey showed five chaises and twenty-four carrying-chairs in town. Stagecoaches soon became a regular part of the scene.

The first stagecoach line was opened in April 1761. It went from Portsmouth, N.H. to Boston via Medford and Charlestown. It had “two good horses,” carried four persons, and was called the “Flying Stage-Coach.” Another line from Salem to Boston was started in 1767. Several others were begun before the Revolutionary War. During the war coach travel was limited but when peace came this mode of traveling flourished again. “With what pleasure these coaches must have been watched as they came along the Salem road, swinging through the marketplace over the bridge, stopping at Royal Oak, Blanchard’s or the Admiral Vernon Tavern.”

TAVERNS

In 1690, Daniel Woodward was licensed by the County Court for a “house of entertainment.” Thomas Willis was the next tavern owner. His place was at the foot of Mann Simond’s Hill and during the next decades a tavern was maintained there by a number of landlords. The Fountain Tavern opened in 1713 and seven years later the Royal Oak opened at the corner of Main Street and Riverside Ave. At one time it had an old swinging sign with a bullet hole in it which tradition says was made by a shot fired from “musket of one of the Minute Men on the return of the Medford Company from Lexington” in April, 1775.

There was also The Admiral Vernon Tavern. The land on which it stood at the corner of Main and Swan Streets was purchased in 1717 and a tavern was erected soon afterward. Under numerous owners, it served the public until 1801 when it became a private home. A fire in 1850 destroyed it. During the Revolutionary War New Hampshire troops made this their headquarters and here John Stark was elected their Colonel.

Blanchard’s Tavern was built in 1752 by Ben Parker. Hezekiah Blanchard took it over in 1776. On its second floor was a room for dancing called Union Hall, popular for “sleighing and dancing parties.” From the ceiling was suspended a model of a full-rigged man of war, the Chesapeake, and its flag bore the dying words of Captain Lawrence, “Don’t give up the ship.” This tavern lasted into the next century and was the terminal of the Medford and Boston Stage Coach Line.

MEDICINE

Simon Tufts began the first doctors practice in 1724. Before him, there had been an Oliver Noyes but Tufts is considered the first established Medford physician. Dr. Tufts sudied at Harvard and earned his degree in 1724. His office was in Medford but he served other towns too until his death in 1747. His son, Simon Tufts, Jr. later became a doctor and took over his father’s practice. In addition to his medical practice the son was a Justice of the Peace, and an occasional member of the General Court. He died in 1782 in a fall from his horse.

The next doctor was Dr. Jonathan Brooks. Born in Medford in 1752, he acquired his medical knowledge from Dr. Tufts. He began work in Reading but after the Revolutionary War opened “a small office on Main Street, near the bridge.” MHSM holds the records to Dr. Brooks’ practice in its collection. Brooks would serve as Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts from 1816-23 and died in 1825.

MEDFORD & the REVOLUTION

A resolution opposing the Stamp Act was passed by the town in 1765. At the Boston Massacre in 1770, John Clark, age 17, a Medford youth was wounded. In 1773 John Fulton, A Son of Liberty, took part in the Boston Tea Party. In 1774 the town voted against serving “any East Indian Tea in our Families.” That same year when the port of Boston was closed by British law Medford businesses were hurt. Yet the town refused to send produce and bricks to Boston until the neighboring towns agreed to do so. Medford’s Representative, Stephen Hall, 3rd, served on a committee to encourage the making of saltpetre (potassium nitrite) used for gun powder.

Medford’s Committee of Safety kept a careful watch on the powder belonging to the town which was stored in the “Powder House,” just south of the Medford town line. Fearing that General Gage would send troops to collect it, they ordered that it be moved to a safer place on August 27th. Three days later Gage did send troops for the powder. Medford citizens now became part of the growing resistance to the King.

In November, the town voted to pay no further province taxes. The taxes were collected and held by the town until early in 1775 when they were ordered turned over to the Treasurer of the Provincial Congress.

Benjamin Hall, a member of the Committee of Correspondence for Medford, served in the last General Court held in Boston before the War. In March he sent to Concord, pork, 50 axes and helves, wheelbarrows and other material for the building of barracks.

Isaac Hall, brother to Benjamin, was leader of the town’s company of Minutemen. The lieutenant was Caleb Brooks, half-brother to the town’s doctor. Old family names such as Tufts, Bradshaw, Francis, Blanchard, Oakes, and Pritchard were represented in this company.

The night of April 18th changed the face of their world. That evening quite by chance as far as Medford was concerned, Paul Revere whose chosen way to Concord was blocked by the British, rode into town over Medford Bridge. He stopped outside the home of Isaac Hall, Captain of the Minute- men, and gave warning that the enemy was on its way to Lexington and Concord. Then he rode off, past the Meetinghouse, to Menotomy to warn the citizens there.

Suddenly Medford was no longer a sleepy rural community. Men whose names have been forgotten were sent to Malden with the alarm. By morning there was hardly a man left in town. The Medford Company (59 strong) and other volunteers marched to Lexington and joined the Reading Company. They fought the British at Merriam’s Corner and followed them back to Charlestown. One Medford man, William Polly, died from wounds suffered in that battle.

Excitement filled the town. “All day the town was astir with drum and fife as company after company marched through toward Concord.” That night Minutemen from various companies bunked in Medford — some of them for their five days of service.

The first company of Medford men was at Cambridge; a second company formed and offered their services to the Committee of Safety. There was some fear that the British might invade Medford up the Mystic River. Cannons were placed on Bunker Hill and fire boats were stationed to prevent such a move by the enemy. Soon a company of New Hampshire soldiers under the command of General John Stark were billeted in Medford.

Two men left town in support of the British. One was Colonel Isaac Royall who happened to be in Boston when the fighting started. He went armed which his neighbors thought suspicious. Events were such that he never returned to Medford although he was always highly thought of by his fellow townsmen. His house became Gen. Stark’s headquarters. The other man to support the British was Joseph Thompson, a local brickmaker. His bricks and lumber were seized by the army.

April turned to June and the Medford Company took part in the battle near Bunker Hill. They watched the burning of the town of Charlestown. That night wounded New Hampshire men were brought to Medford and a field hospital was established south of the bridge. Among the women who helped care for the injured was Sarah Bradlee Fulton.

During the next several months much activity took place in and around Medford. Entrenchments were built on Winter Hill, spades and shovels were provided for the soldiers by the town folk. When Washington took command of the new army, one thousand men were stationed in the Medford area. There was alarm after alarm, rumor after rumor. No one knew just what the British might do. As winter came, the trees in the “Charlestown Wood Lots” helped keep the patriots warm. Medford became one of the towns that provided shelter for the homeless folk from burnt-out Charlestown and for persons fleeing Boston. Sarah Fulton who had helped the patriots before, helped again by carrying messages to and from Boston during the siege of that town. Later, Fulton Street was named in her honor.

In March 1776, the British left Boston and the fury of the war moved out of Massachusetts. Medford men fought in many of its battles and endured its hardships. They were at Ticonderoga, at Morristown, at Stillwater where Francis Tufts took up the flag which had fallen during the battle and bore it proudly. They wintered at Valley Forge with Washington. They were not always treated with honor. John Symmes came home “ragged and emaciated.” His pay bought a yoke of oxen. When he sold them the money he got was so worthless it would buy only “a bag of Indian meal.” Still Medford men continued to enlist and fight for their freedom. Medford welcomed with happiness the Declaration of Independence read by David Osgood from the pulpit the Sunday after it was received. More than two hundred men, some enlisting more than once, served in the war.

On October 19, 1781 Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown. The news reached Medford on the 26th. It was believed by everyone except the minister. Osgood wanted it confirmed by some authority. By the next day even he was satisfied. Gradually the soldiers came back to their farms, their shops, the river. Life returned to normal in Medford. But no one alive ever forgot the great struggle they had been engaged in; and they lived to treasure their new freedom, the right to their own government. In Osgood-s phrase: they heard the “sound of peace.”

If the Sprague brothers had revisited Medford at the end of the eighteenth century, they probably would have ridden into town in a chaise — a more convenient way to travel from Salem. They would have found a town with five times the population of the seventeenth century village; a town that had nearly doubled in area by adding a part of Charlestown. They would have found its inhabitants organized with civic services and essentially a contented group of people. For as one observer wrote about those days — “A long period of happiness at last arrived in the times of Turrell and Osgood; and for more than a century, Medford has appeared one of the most thriving villages in the vicinity of Boston.”

With excerpts from Medford on the Mystic. By Carl Seaburg and Alan Seaburg. Published by The Medford Historical Society, April 1980.